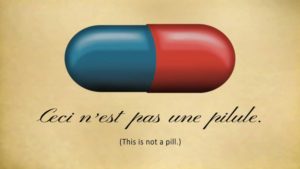

Well, somebody bit the bullet and came clean with their claims for a non-alcoholic beer: it’s a placebo! Yes, Placebo Beer is now on tap in Houston, Texas.

“Angela, one of our brewers here at Urban South, is the mastermind behind this new series,” said Dave Ohemer, General Manager of Urban South – HTX. “We noticed an increasing number of our guests were non-alcohol drinkers who still wanted to visit the brewery with friends and family for the atmosphere or to enjoy some of our local food options. Our brewing team is excited for the opportunity to experiment with some of the ingredients we use in our fruited sours and create an option for this growing audience. We’ve received great feedback so far and look forward to continuing to develop the Placebo Effect series.”