We’re creatures of our times here at Universal Placebos, so we had to get amongst ChatGPT on the topic of placebos.

Universal Placebos:

Write a blog post on the pros and cons of using placebo medication.

ChatGPT:

Introduction:

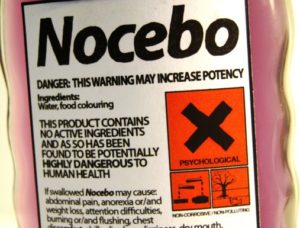

Placebo medication is a type of treatment that is often used in clinical trials to test the effectiveness of new drugs or treatments. It is a substance that looks and tastes like a real medication, but does not contain any active ingredients. The purpose of a placebo is to create a control group for comparison, allowing researchers to determine whether a new drug or treatment is truly effective. In this blog post, we will explore the pros and cons of using placebo medication.

Pros:

- Creates a Control Group: One of the most significant benefits of using placebo medication is that it creates a control group that can be used for comparison. In clinical trials, researchers typically divide participants into two groups: one group receives the new drug or treatment, while the other group receives a placebo. By comparing the outcomes of the two groups, researchers can determine whether the new drug or treatment is effective.

- Minimizes Bias: Another benefit of using a placebo is that it can help minimize bias in clinical trials. When participants know that they are receiving a new drug or treatment, they may have higher expectations for its effectiveness, which can skew the results. Placebos can help prevent this by creating a more objective comparison between the two groups.

- Safe: Placebo medication is safe and has no side effects, which makes it an ideal choice for use in clinical trials. In contrast, some drugs and treatments can have serious side effects, which can be harmful to participants.

Cons:

- Ethical Concerns: One of the main ethical concerns associated with using placebo medication is that it involves deceiving participants. Participants are often not informed that they are receiving a placebo, which raises questions about whether they have truly given informed consent. While some argue that this is necessary to ensure the integrity of the trial, others argue that it is unethical to deceive participants in this way.

- Limited Use: Another disadvantage of using a placebo is that it can only be used in certain types of clinical trials. For example, it is not possible to use a placebo when testing the effectiveness of surgery or other invasive procedures. This limits the applicability of placebo medication as a research tool.

- Reliability Issues: Finally, there are concerns about the reliability of placebo medication as a control group. Some argue that the placebo effect (the phenomenon in which a person experiences a perceived improvement in symptoms simply because they believe they are receiving treatment) can skew the results of clinical trials. This can make it difficult to determine whether a new drug or treatment is truly effective.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, placebo medication has both pros and cons when it comes to its use in clinical trials. While it can create a control group and minimize bias, it also raises ethical concerns and has limited use in certain types of trials. Ultimately, the decision to use a placebo should be made on a case-by-case basis, taking into account the specific circumstances of the trial and the ethical considerations involved.

Universal Placebos:

For which conditions and under what circumstances might be consider a placebo treatment for a complaint?

ChatGPT:

Placebo treatments are typically used in clinical trials as a control group to determine the effectiveness of a new drug or treatment. However, in certain cases, placebo treatments may also be used as a therapeutic intervention for a complaint. Here are a few examples of conditions and circumstances where placebo treatment may be considered:

- Pain Management: Placebos have been shown to be effective in reducing pain in some cases. They may be used as a complementary treatment in conjunction with other pain management strategies, such as physical therapy or medication.

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): IBS is a condition that can be difficult to treat, and many patients experience symptoms that are not fully relieved by medication or other therapies. Placebo treatments have been shown to be effective in reducing symptoms in some patients with IBS.

- Depression: Placebo treatments have been used in clinical trials to test the effectiveness of antidepressant medication. However, some studies have also shown that placebo treatments can be effective in reducing symptoms of depression on their own.

- Anxiety: Placebos have also been used in clinical trials to test the effectiveness of anti-anxiety medication. However, some studies have shown that placebos can also be effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety.

- Sleep Disorders: Placebos have been used in clinical trials to test the effectiveness of sleep medication. However, some studies have shown that placebos can also be effective in improving sleep quality.

It is important to note that the use of placebo treatments as a therapeutic intervention is still controversial, and there are ethical considerations to take into account. In general, it is important to discuss the potential risks and benefits of placebo treatments with a qualified healthcare provider before considering this type of intervention. It is also important to note that any use of placebo treatments should be transparent and fully informed, with patients fully understanding the nature of the treatment they are receiving.

Universal Placebos:

Do you have an opinion on the efficacy of placebo treatments?

ChatGPT:

As an AI language model, I don’t have personal opinions or beliefs. However, I can provide information on the scientific consensus regarding the efficacy of placebo treatments.

Placebo treatments have been shown to have some level of effectiveness in reducing symptoms in various conditions, including pain, depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders. The exact mechanism by which placebo treatments work is not fully understood, but it is thought to involve a combination of psychological and physiological factors.

Some studies have found that the placebo effect can be quite powerful, with some patients experiencing significant improvements in symptoms even when they are aware that they are receiving a placebo. Other studies have suggested that the placebo effect may be more modest, and that factors such as the severity of the condition being treated and the expectations of the patient may play a role in determining the magnitude of the effect.

It is important to note that while placebo treatments may be effective in reducing symptoms, they are not a substitute for evidence-based treatments. In some cases, placebo treatments may be used in combination with other therapies, such as medication or cognitive-behavioral therapy, to provide additional symptom relief.

Overall, the scientific consensus is that placebo treatments can be effective in reducing symptoms in some cases, but the exact magnitude of the effect may vary depending on the specific condition being treated and the individual patient. It is also important to note that the use of placebo treatments as a therapeutic intervention raises ethical concerns, and should be done with full transparency and informed consent.