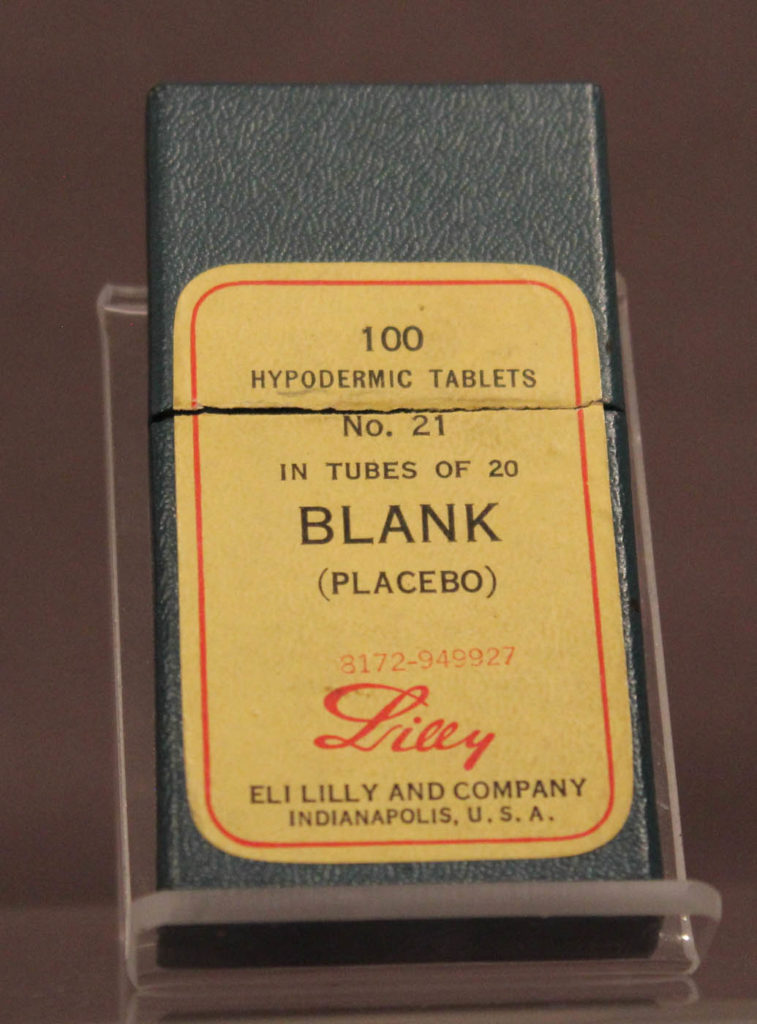

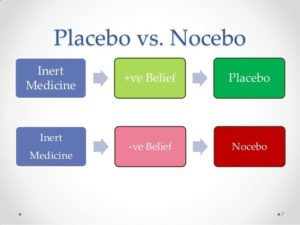

Scientists have come up with a new name for experiments that utilize placebos

Trick or treatment

+++++

I’m addicted to placebos.

I could quit but it wouldn’t matter.

+++++

On my way home from work today I was listening to Placebo..

I thought I was listening to something else, but obviously I was the control group.

+++++

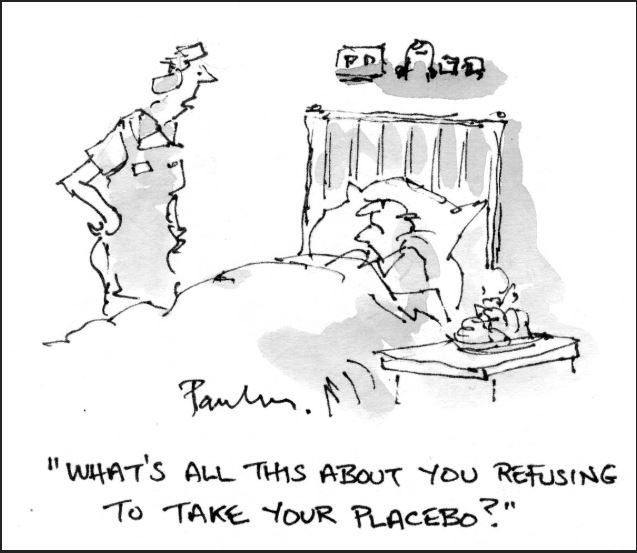

Is that placebo working for you?

Well, now that you mention it, no.

+++++

My doctor is concerned my hypochondria is getting worse

So he put me on stronger placebos.

+++++

I got in trouble for using performance enhancing drugs

I took a placebo before my psychology exam

+++++

I was part of a scientific study on the calming effects of listening to the Three Tenors.

I felt great, but was in the control group. It turns out I was listening to Placebo Domingo.