It may be that the placebo effect is ‘not all in your head’. Findings from a new study indicate distinct physiological effects related to the perception of pain, according to a patient’s belief that a cream applied to their arm was either generating heat (the ‘nocebo’ option), numbness (the ‘placebo’ option) or no change (the ‘control’). All of the ‘creams’ were actually Vaseline. (Ref. Brainstem mechanisms of pain modulation: a within-subjects 7T fMRI study of Placebo Analgesic and Nocebo Hyperalgesic Responses, The Journal of Neuroscience)

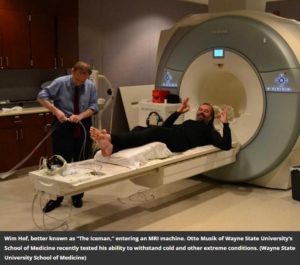

The Australian researchers measured brainstem activity with high-resolution functional MRI (fMRI) in participants as they rated the pain of a hot stimulus applied to their arm.

From this article: “Over two successive days, through blinded application of altered thermal stimuli, participants were deceptively conditioned to believe that two inert creams labeled ‘lidocaine’ (placebo) and ‘capsaicin’ (nocebo) were acting to modulate their pain relative to a third ‘Vaseline’ (control) cream.”

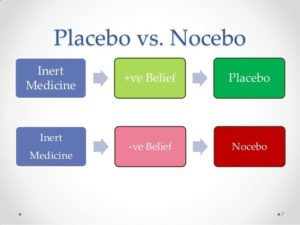

Placebo and nocebo effects influenced activity in the same brainstem circuit but in opposite ways. The strength of the placebo effect was linked to increased activity in an area called the rostral ventromedial medulla and decreased activity in a nucleus called the periaqueductal gray; the nocebo effect induced the opposite change. These results reveal the role of the brainstem in pain modulation and may offer a route for future treatments of chronic pain.

“Placebo and nocebo effects influenced activity in the same brainstem circuit but in opposite ways. The strength of the placebo effect was linked to increased activity in an area called the rostral ventromedial medulla and decreased activity in a nucleus called the periaqueductal gray; the nocebo effect induced the opposite change. These results reveal the role of the brainstem in pain modulation and may offer a route for future treatments of chronic pain.”