A recent ‘meta-study’ claims that placebo are NOT, in fact, on par with conventional antidepressant medications, as we have reported numerous times in this blog. It seems, however, that this study should be read with certain caveats, most particularly that “The review’s authors have acknowledged that almost 80% of the studies they analysed had been funded by the pharmaceuticals industry.” (Fawning Coverage of New Antidepressants Review Masks Key Caveats) Confirmation bias, anyone?

Tag Archives: Latest

Sex Differences in the Placebo Effect?

Do males and females respond differently to the placebo effect? This review of 18 studies concludes that “1) males responded more strongly to placebo treatment, and females responded more strongly to nocebo treatment, and 2) males responded with larger placebo effects induced by verbal information, and females responded with larger nocebo effects induced by conditioning procedures.”

Why?

It seems “that … differences in the placebo and nocebo effects (are) probably caused by sex differences in stress, anxiety, and the endogenous opioid system.”

Download the study ‘A systematic review of sex differences in the placebo and the nocebo effect’

Do Worms Experience A Placebo Effect?

No, seriously, do they?

“Is the placebo effect biologically real? We’re not sure. But, if it is, then it is safe to say that it evolved over time, that it confers some survival advantage, and most importantly, it should also be able to be seen in other organisms. It has been reported in rats on occasion. But, what if we could study the placebo effect in lower organisms like fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) or worms (Caenorhabditis elegans)?

In the study of aging, these tiny, but powerful animals who age quickly, make it easier to do many experiments in a shorter period of time. Worms, in particular, are a fantastic model for the field of dietary restriction (DR), a programmed method of reducing calorie intake and the most scientifically sound method of extending lifespan. But in worms, the extended lifespan offered through DR is disrupted by the smell of food which tricks their bodies out of DR mode and stops the extension of life.”

Check out Simon C. Harvey, Chris J. Beedie, “Studying placebo effects in model organisms will help us understand them in humans” Biology Letters. 29 November 2017 or read the ACSH article here.

Want to think outside of the box? Try sniffing a placebo

We usually think of placebos as tools for therapy, or perhaps as marketing strategies, but here’s an idea about the placebo effect and creative thinking.

“The placebo effect is best known in medicine for making people feel better when they are given sham treatments. Now there is growing interest in using placebos to boost athletic and cognitive abilities.

Previous studies have found that people lift more weight and cycle harder when they take medicines with no active ingredients that are falsely labelled as performance-enhancing substances. Placebo pills have also been shown to improve scores in memory tests.

These findings prompted Lior Noy and Liron Rozenkrantz at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel to test whether the placebo effect can stimulate creativity too.

They asked 90 university students to sniff a substance that smelled of cinnamon. Half the students were informed that the substance had been designed to enhance creativity.

The participants then completed a series of tasks designed to test their creativity. One involved rearranging squares on a computer screen into different shapes. Another required them to think up new uses for everyday items like shoes, pins and buttons.

Those who were told the smelly substance increased creativity scored higher on measures of originality. For example, they came up with more unusual shape configurations and novel applications for the everyday items. “The improvements weren’t enough to turn you into the next Picasso, but they were significant,” says Noy.”

Read the full article here.

Placebos and anti-depressants in children and teenagers

A recent ‘meta-analysis’ of the placebo effect on the use of anti-depressants in children and adolescents (shudder …), based on data from trials involving more than 6,500 children and adolescents up to the age of 18, has been published by the University of Basel and Harvard Medical School and published in the journal ‘JAMA Psychiatry’.

The most common mental disorders in children and adolescents include anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

“The results of the meta-analysis show that, although antidepressants work significantly better than placebos across the range of disorders, the difference is small and varies according to the type of mental disorder. However, the results also showed that the placebo effect played a significant role in the efficacy of antidepressants. The study also found that patients treated with antidepressants complained of greater side effects than those who received a placebo. The side effects included everything from mild symptoms such as headaches to suicidal behavior.”

‘Suicidal behaviour’ as a ‘side effect’ … Really?

Consistent with other posts through this blog, the analysis also shows that the placebo effect is stronger in cases of depression.

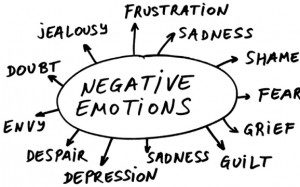

The placebo’s evil twin

The placebo effect is one of the most mystifying phenomena in medicine. When we expect a pill to make us feel better, it does. If we see others get better while using a medicine, we will too.

But the placebo effect has an evil twin: the nocebo. It can kick in when negative expectations steer our experience of symptoms and create side effects where none should occur.

This means, incredibly, that you can get side effects from a sugar pill. And sometimes these side effects are so severe that patients drop out of clinical trials. More info here.

Recent evidence suggests that the muscle aches might be a big nocebo.

More Research on ‘Open Label’ Placebos

Whether you know you’re taking a placebo pill or not, it will still have a beneficial effect, new research has revealed (Is the rationale more important than deception? A randomized controlled trial of open-label placebo analgesia.)

Scientists from Harvard University and the University of Basel prescribed a group of minor burn victims with a “treatment” cream, telling only some of them that it was a placebo.

After the cream was applied, both groups reported benefits, despite the placebo cream containing no medicine.

Read the full article here

On the subject of Open Label Placebos, here’s a link to research on their efficacy in chronic lower-back pain.

Who is More Likely to Experience a Strong Placebo Effect?

A new study finds that people who have a better handle on their negative emotions may be more likely to experience a stronger placebo effect. Researchers at the University of Luxembourg found that participants who were better at interpreting negative events in a positive light felt more relief from a placebo pain-relieving cream.

The placebo effect has traditionally been viewed in a negative light; however, within the last decade, researchers have investigated the placebo effect itself and found that placebos can trigger real biological changes in the body, including the brain.

“All participants reported less pain: the placebo effect was working. Interestingly, those with a higher capacity to control their negative feelings showed the largest responses to the placebo cream in the brain. Their activity in those brain regions that process pain was most reduced. This suggests that your ability to regulate emotions affects how strong your response to a placebo will be.”

‘Branding acts like a placebo’

“Branding acts like a placebo. It changes consumer perception and, in turn, those perceptions alter the nature of the product.”

Read the fascinating story of Lieutenant Colonel Beecher here (as well as a commentary on the placebo effect in marketing).

A recent example? The internet recently has been alive with stories about research into the placebo effect and our apprehension of the quality of wine – and, perhaps worryingly for some, the brain functions which govern our actual experience of its taste! (Hint: higher price = higher quality).

Here’s a sample article: Why expensive wine appears to taste better: It’s the price tag. The authros point out:

“Price labels influence our liking of wine: The same wine tastes better to participants when it is labeled with a higher price tag. Scientists have discovered that the decision-making and motivation center in the brain plays a pivotal role in such price biases to occur. The medial pre-frontal cortex and the ventral striatum are particularly involved in this.”

PLACEBO AND FAKE SURGERY

Two thought-provoking articles relating the placebo effect to ‘sham surgery’, which has been canvassed in these pages previously.

In this meta-study, the authors point out that ” the literature is not chock full of studies comparing a surgical procedure to placebo. While the study of a drug versus placebo is standard practice, the picture changes radically when the placebo is a sham operation involving incisions and anesthesia … Of about 3000 articles, 53 full-text articles were selected. They represented randomized controlled studies, with both an active intervention and a placebo arm involving a sham procedure. The authors defined a surgical outcome based on three elements:

• The critical surgical component – the anatomic changes felt to result in a therapeutic effect

• Placebo component – the patient’s expectations

• Non-specific effects – changes in the natural history of an illness that might impact the outcome, the experience of being in a hospital, interactions with staff – the multitude of other factors.

In this study, the author admits that sham (placebo) srugery already occurs. Because it can work.

How?

“How can sham surgeries work? Bigness. In the same way that placebo pills and other modalities make people get better, the clinical evaluation, workup, stress and travel of surgery day, surgical prep, etc. all make for an almost unbeatable set of placebo-instituting conditions. And with some of the data which exist, sham surgeries perform better in the patients’ minds than a drug treatment that’s a comparator for the same condition.