Tag Archives: Latest

To Use Or Not To Use The Term “Placebo,” That Is (Not) The Question

Like the word dirge, placebo has its origin in the Office of the Dead, the cycle of prayers traditionally sung or recited for the repose of the souls of the dead. The traditional liturgical language of the Roman Catholic Church is Latin, and in Latin, the first word of the first antiphon of the vespers service is placebo, “I shall please.” This word is taken from a phrase in the psalm text that is recited after the antiphon, placebo Domino in regione vivorum, ”I shall please the Lord in the land of the living.” The vespers service of the Office of the Dead came to be called placebo in Middle English, and the expression ‘sing placebo’ came to mean “to flatter, be obsequious.” … Placebo eventually came to mean “flatterer” and “sycophant.”

The term entered medical history in the late 18th century, with a few British doctors that can claim to be the originator. For one, there is Alex Sutherland (born before 1730 – died after 1773) a doctor living and practicing in Bath, Summerset, who used the term to describe certain types of doctors keen to prescribe fashionable medicines such as waters with healing power, which he called “placebo” (doctors) in a popular book published in 1763. About the same time, William Cullen (1710 – 1790) from Edinburgh, Scotland, used it for the first time in a textbook, his Clinical Lectures: He gave a patient mustard powder as a remedy noting “… that I did not trust much to it, but I gave it because it is necessary to give a medicine, and as what I call a placebo,” summarizing today’s entire discussion in a single sentence: Placebos are to please the patient and improve symptoms because of that – what we call the placebo effect. And the third gentleman is John Coakley Lettsom (1744-1815), a doctor from London who resumed a similar position to Cullen; they used placebos of ineffective doses of what were popular medicines of their time.

More on this fascinating history, including the inclusion of placebo in the earliest forms of homeopathic practice, here.

Preventing Nocebo Effects

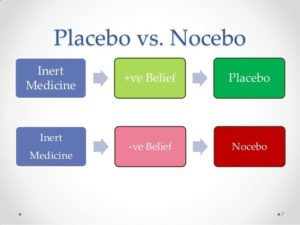

We all know about the ‘nocebo’ effect by now – the dark twin of the beneficial placebo effect. For example, a study showed that the pharmacological efficacy of remifentanil (a pain medication) was significantly decreased after patients were told the infusion was stopped during a heat-pain modulation test. Although the infusion had not actually been halted, participants experienced a significant exacerbation of pain even while still receiving remifentanil.

To counter undesirable ‘nocebo’ effects, this article suggests to health practitioners that ‘pragmatic strategies related to patient–practitioner interaction, clinical setting, and context may be implemented to help minimize and prevent the consolidation of negative expectations’.

Receiving DNA test results can actually alter your physiology

There is some evidence – for example, in this study – that simply receiving the results of DNA tests can have a physical impact. Why? Well, once more the Placebo Effect is mentioned (as well as its dark twin, the Nocebo Effect, also covered on this website.

DNA tests are becoming quicker, cheaper and more reliable, so this is an issue we’ll hear more about.

Placebos and Pain

Pain is something of a mystery. While we all experience it, and experience it in degrees, there’s no ‘gold standard’ for estimating the degree of pain. It seems to be a ‘subjective’ experience. In some of the research literature, such as this study, the placebo effect is given a credible place in the landscape of pain and pain management.

“Placebo effects that arise from patients’ positive expectancies and the underlying endogenous modulatory mechanisms may in part account for the variability in pain experience and severity, adherence to treatment, distinct coping strategies, and chronicity. Expectancy-induced analgesia and placebo effects in general have emerged as useful models to assess individual endogenous pain modulatory systems.”

Meantime, in the category of ‘Out There But Maybe Not As Out There As You Might Think’ virtual reality may have the capacity to harness the placebo effect in pain management.

“Recently, Cedars-Sinai also published research on the clinical utility of a virtual reality intervention in the Inpatient setting. The results of the study were overwhelmingly positive with most patients receiving pain and stress relief from the VR experience.”

More on VR applications here.

Nocebo Effects: How to Prevent them in Patients

We’ve posted elsewhere about the placebo’s dark twin, the nocebo, the phenomenon of the mind provoking negative and damaging effects through the same mechanism that accounts for the positive effects of a placebo.

This paper brings focus to ‘nocebo algesia and hyperalgesia (ie, the occurrence and worsening of nocebo-induced pain, respectively)’ and makes practical suggestions for reducing the incidence of this. As always, these relate to the patient-practitioner relationships and interactions, and strongly reinforce the ‘subjective’ and ‘negotiated’ nature of the experience of pain.

‘In general, the literature shows that uncaring interactions that convey a message of invalidation and lack of warmth may trigger nocebo effects. Avoiding negative communication and interactions with a patient may help to shape a safe and positive environment that not only promotes placebo effects but that also reduces nocebo effects.’

Expectations and the Placebo Effect

What you expect is often what you get, and the placebo effect is at work! We have noted elsewhere that one possible account for the engagement of the placebo effect is the wish to ‘please the physician’, to be a ‘good patient’. According to this Stanford study, this might come as only a few positive words. “… When a health care provider offers a few encouraging words about their patient’s recovery time from an allergic reaction, symptoms are significantly reduced.”

Similarly expectations about the benefit of exercise can be seen to actually impact on life expectancy outcomes. In this study “the team looked at death rates. They used statistical models to account for other factors linked to death, such as age, chronic illnesses, and body mass index (BMI). Even accounting for these risk factors, those who saw themselves as less physically active were 71% more likely to die in the 21 years following the original survey.”

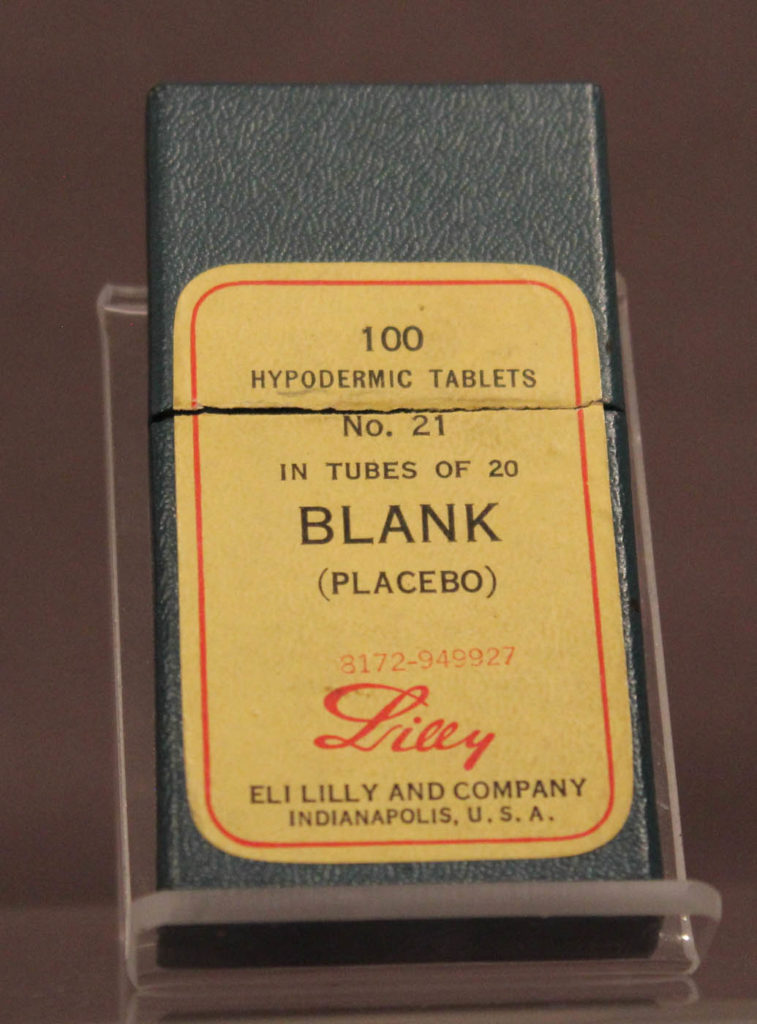

Open Label Placebos … again

An article in Big Think entitled People are knowingly taking placebos—and its working starts to untangle some of the theories about the functionality of ‘open label’ placebos – which describes the engagement of a placebo effect even when people know they’re taking a placebo.

“Even though they were told that what they were taking was placebo and contained nothing of therapeutic value, those patients who received the placebo reported a 30% reduction in usual pain and maximum pain and a 29% drop in their disability. Incredibly, the placebo worked better than the real pain medication. Participants who took the pain pills reported feeling 9% less usual pain, and 16% less maximum pain. Furthermore, patients taking the real medication reported no change in their level of disability.”

Placebos and pain

Pain is a subjective state – that’s why practitioners typically ask us to ‘scale’ our experience of it, from a ‘1’ (slight) to a ’10’ (unbearable). And while it’s easy to see why the experience of pain is useful in an evolutionary sense (‘keep your hand out of the fire!’) it’s difficult to account for what mechanism is responsible for this experience. Different analgesics may have different effects (and affects) for different people, and some don’t seem to contraindicate – it seems you can ingest an opioid at the same time as paracetemol.

Enter the placebo effect! Here’s a recent research paper on placebos and pain. And also a fascinating article on ‘leveraging the Placebo Effect to Reduce Opioid Requirements’.

So you have a placebo-friendly brain and personality?

It seems there may be characteristics which not only how receptive you are to benefiting from the placebo effect, but also the degree with which it effects you.

In a study published in Nature Communications, two factors seems to influence results:

- Brain anatomy (such as asymmetry in areas of the brain that control emotion and reward, including the amygdala, accumbens and hippocampus), and

- ‘Personality’ – especially mindsets “emotionally self-aware, attuned to the body and mindful of one’s surroundings”

At Universal Placebos we’ve always known that awareness and mindfulness are part of the therapeutic value of placebos, of course, which is why our product comes bundled with instructions for mindful and meaningful administration.

“Down the line, the clinician could give five or six questions to the patient and decide whether they should just prescribe a sugar pill to them,” say the researchers. “The higher they score on this personality questionnaire, the bigger their placebo response will be.”